A couple of months ago the National Mental Health Commission released their full report after sections were leaked to the media ahead of the Federal Budget in May. The report makes it clear that hundreds of people wrote in calling for better access to psychological care via the Medicare system. Some of the bigger issues on this topic are how many sessions of therapy should be available, and who should be eligible to provide psychological care. Another challenge is how we can provide psychological care to distant locations in a nation as vast as ours.

The NMHC report highlights multiple problems around the provision of psychological care in regional, rural, and remote Australia. Volume 3 of the review summarised public feedback received by the NMHC on this topic (pages 125-134). The report identifies that in distant places there is generally a lack of access to support, a shortage of therapists, higher numbers of people in distress, greater levels of stigma, and difficulties remaining anonymous if one does seek help. This section also identifies issues around rigid service models which don’t reflect the realities of life in these regions, and no funding to account for the additional costs of providing services in those places. The Commission made several recommendations to address these problems in the Medicare system. In the following short article I will critically examine those recommendations and offer my own suggestions for change.

Proposed actions

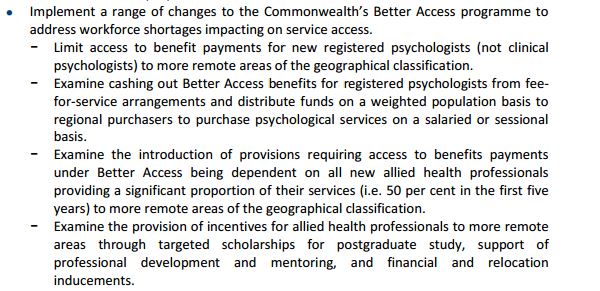

Recent commentary over news and social media give the impression that the recommendations of the Commission are clear and wholeheartedly supported by the mental health sector, but that is hardly the case at all. At this point I’d encourage all of you to read the actual list of actions recommended to address the problems highlighted above (Volume 2, page 107). I’m going to focus on the section relating to the Better Access to Mental Health Care program. Hopefully this will illuminate why the proposed actions for reform are in themselves quite problematic. Here is a screen capture of the listed recommendations:

The first thing I noticed here is how vague the recommended actions are. It should really be no surprise to anyone that the list is going to take a bit of time to work out the fine details before we end up with any specific policies. In my opinion, the recent calls to implement change immediately are politically driven. It’s all about pushing through policy agendas while the current key opinion leaders still have access to the microphone. The effect is to apportion guilt to the current Government if change isn’t implemented right away. It’s important to read the fine print to see why that might be the case.

Punitive incentives?

Three of the listed actions recommended by the Commission appear to be punitive measures. They are restrictions rather than incentives to work in distant parts of Australia. Restrictions tend not to function as a way of encouraging people. There’s a good chance that psychologists will simply choose to find work elsewhere if we discourage them from taking up opportunities in regional, rural, and remote Australia. Given that one of the identified problems in those locations are a shortage of therapists, it is difficult to understand how limitations could improve mental health care. In any case, let’s look at each recommendation.

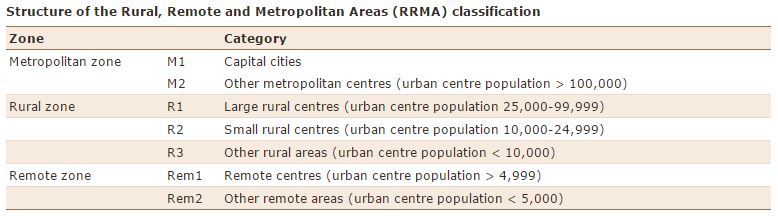

The first proposal is to force psychologists to work in remote areas by preventing them from getting a Medicare provider number unless they go to a remote area. There are two issues that need to be highlighted here. First, the Commission makes a point of deliberately excluding clinical psychologists. Second, the wording of the proposal suggests that they are talking about the geographical classification system shown below (sourced from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare):

If we are seriously going ahead with the plan, then personally, I can’t think of any good reason why clinical psychologists should be excluded from the proposal. Consider the finding that people living in these areas experience a lack of access to support, a shortage of therapists, and that there are a higher proportion of people living with a mental health condition. If this measure is truly intended as a way to increase access to psychological care, then how can we justify excluding clinical psychologists from those arrangements?

With regards to the zones of geographical classification, the wording of the proposal was very specific about naming remote locations but did not mention rural zones. I think this is worth noting too because similar problems are being faced by rural areas. If this solution to the shortage of therapists is appropriate for remote locations, then why are they not also deemed appropriate for areas classified under the rural zone? It is possible that by the phrase “more remote” the Commission intends to include some rural zones. It is also possible that the Commission was referring to the ASGC-RA system for classifying remoteness, although, all of the issues mentioned here would still apply anyhow. What is plain to see is that this vaguely worded proposal needs further work to draw out exactly what is intended. In addition, I think there is considerable room for debate on which zones should be included before we proceed any further.

The second proposal refers to “cashing out” Medicare items to generate salaried funding packages for regional purchasers. In plain language, that means that Primary Health Networks (aka ‘Medicare Locals’) and other private bodies could purchase psychological support services and send the bill to Medicare. There’s a lot of room in there for obfuscation, where Medicare could end up footing the bill for say, 8 hours per day across a week, to pay for the salary of a psychologist who may only end up seeing a few clients per day. If statistics from the Australian National Audit Office are anything to go by, then around 25% of that funding is likely to be routinely re-directed to administration (page 53) – and of course there would be other costs to cover in the regional, rural, and remote setting. Once again though, it isn’t clear what the Commission meant by the phrase “cashing out”. We would need a lot more information to make sense of the proposal before deciding whether the plan is a good one.

The third proposal appears to extend the first proposal to all new allied health professionals. It recommends that at least 50% of services must be delivered to remote areas in the first 5 years of registration as a Medicare provider. According to the Department of Health the term ‘allied health professional’ includes a long list of professions, however in this case the proposed action is limited to the scope of Medicare, which would include all psychologists, social workers, and occupational therapists working in the Better Access to Mental Health Care scheme. Given the other recommendations of the Commission, this proposal could potentially also include speech pathologists and mental health nurses. Honestly, this plan seems a bit steep and very hard to implement without discouraging therapists from seeking registration as a Medicare provider. Overall this plan will lead to less Medicare providers offering psychological care and is likely to cause a constant exodus of practitioners from regional, rural, and remote areas once their 5 years is up. There is also likely to be quite a lot of resentment about having to stay for 5 years. It doesn’t sound mentally healthy to me having our mental health professionals feeling resentful at being forced to spend the first 5 years of their career away from town if that is where they’d prefer to be.

My recommendations

Some of you may have noticed that it has taken me a lot longer to respond to these proposals from the Commission. The reason is that I wanted to consult broadly, with members of the public and my colleagues, before generating ideas for change. I don’t have all of the solutions, but I think we came up with some great ideas that policy people can work with. If you have more ideas, please let us know in the comment section below. In general, you’ll notice that the suggestions we came up with align with the fourth proposal of the Commission, which emphasises the creation of incentives to encourage and motivate people to work in distant places. I think that makes a lot more sense than setting up more red-tape if our goal is to bring mental health care professionals to geographically distant areas and keep them happily staying there in the years ahead.

Some of you may have noticed that it has taken me a lot longer to respond to these proposals from the Commission. The reason is that I wanted to consult broadly, with members of the public and my colleagues, before generating ideas for change. I don’t have all of the solutions, but I think we came up with some great ideas that policy people can work with. If you have more ideas, please let us know in the comment section below. In general, you’ll notice that the suggestions we came up with align with the fourth proposal of the Commission, which emphasises the creation of incentives to encourage and motivate people to work in distant places. I think that makes a lot more sense than setting up more red-tape if our goal is to bring mental health care professionals to geographically distant areas and keep them happily staying there in the years ahead.

The first specific policy idea is to provide specially-targeted scholarships for trainees who actually live in rural, regional, and remote locations. The idea is that people who already identify with a community in a distant part of Australia are encouraged to bring their skills back home. One component of the scholarship is that the recipient would be supported for the first 3 years of work when they return back to the regional, rural, or remote area. Offering supported work opportunities at the end of training as a mental health professional will assist the trainee to merge their new professional identity with their existing sense of self as a valued member of the community where they originally came from.

The second idea we had to assist with that process was to invest in technology and training procedures that allow for distance education in mental health training. The aim is to help people who are already living in a distant part of Australia to pursue a career in mental health care without needing to leave town for 3 years or more. There are of course some practical and technical challenges with putting such a plan into action, however, I do not believe those barriers are insurmountable. With a little planning and investment, systems could be established such that much of the training can be conducted online, with additional focused supervision and training directed specifically at those trainees in distant locations. Some placement opportunities may require periods of time away, however, emphasis could be placed on directing those trainees to placement opportunities which are relevant to their own community.

The third proposal is simple – a higher Medicare rebate for psychological services in rural, regional, and remote areas. Setting a higher Medicare rate for services in distant locations will serve two main functions: (1) it will attract currently city-based psychologists to work further afield and (2) it will reduce out of pocket expenses by driving down gap fees. This recommendation could also potentially be used to factor in the cost of travel, resolving a long-standing problem which has kept most therapists shackled to suburban areas. This proposal will make it easier for city-based therapists to leave suburbia and seek new challenges and opportunities where psychologists are very much needed.

My fourth suggestion is to provide additional funding and support for professional development and supervision in distant regions. National registration requirements demand ongoing professional learning, which is next to impossible to access for those mental health professionals who work outside metropolitan areas. At present that’s a huge disincentive for therapists planning on moving away from town. Additional funding to cover some of the extra costs of travel and time away from work could reduce the disadvantage faced by those practitioners.

Our final proposal is to offer registrars a pathway to cover the costs of supervision and related professional development if they undertake their registrar period in a rural, regional, or remote part of Australia. For psychologists, the registrar period is a particularly challenging time. The additional cost of getting registrar supervision is severely taxing at a time when a psychologist is just starting to find their feet. Conversely, we know that psychologists are in short supply in geographically distant regions, leading to overwork and early burn-out for many practitioners. A logical solution to both problems would be to connect psychologists in geographically distant places with trainees who are willing to complete their registrar period away from the big cities. The solution could be as simple as providing a web-based network connecting these two groups of people together. With a little support and some incentives to make the arrangement mutually beneficial, registrars could potentially fulfill all of their requirements for full registration, whilst at the same time reducing over-stretched local practitioners who often serve their community in complete isolation. As with the policy ideas outlined above, the registrar gets a taste of the nature of work. Some will choose to stay as they become part of that community.

The essence of all of these ideas is that we want to encourage people to work in rural, regional, and remote parts of Australia. In my opinion, limitations and restrictions are not the way to go about that – what do you think? Your comments and ideas for change are welcome below.

NOTE: I would like to take a moment to send a BIG thank you to everyone in the Alliance for Better Access Facebook group who helped us generate these ideas. Very much appreciated!

betteraccess

Update: We have identified one part of the report which aligns with our suggestion that the system needs to offer better incentives for mental health professionals when they deliver psychological care to rural areas (Volume 1, Recommendation 13, page 97 http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/media/119905/Vol%201%20-%20Main%20Paper%20-%20Final.pdf):

“The lack of rural incentives under Better Access appears to be an anomaly when

compared with other programmes where there is a rural loading—for example, for

GPs, practice nurses and mental health nurses.”

This is interesting when we put it alongside of another recommendation made earlier in the same section (page 96):

“Examine cashing out Better Access benefits paid for services provided by registered psychologists who do not have an additional endorsed qualification and distributing those funds on a weighted population basis to regional purchasers for psychological services on a salaried or sessional basis.”

betteraccess

Another Update: We also noticed today that the report also names the regional classification system they intend to use to define “remote” areas. It’s the Modified Monash Model – take a look at http://www.doctorconnect.gov.au/internet/otd/publishing.nsf/content/classification-changes

betteraccess

The latest issue of the NSW Medical Students Council magazine ‘Rubix’ discusses the negative impact of using scholarships to coerce medical students to live and work in rural areas for 6 years (http://issuu.com/aj.jessyang/docs/web_rendering/14?e=0). This is very similar to the plan we see from the National Mental Health Commission to restrict psychologist registration unless the new trainee lives and works in a remote location for 5 years. The magazine article describes the MRBS scholarships as “ineffective and coercive” saying that eradicating the scheme was a step in the right direction. The author points out the following:

“Fortunately, we do have evidence to support effective strategies. It is well-established that a rural background and positive rural experiences throughout medical school are the two main factors that affect the decision to practice rurally.”

Here’s a screen capture for those who might have trouble with the link above: