At the beginning of the year Medicare appointments for psychological treatment were cut down to just ten sessions. These cuts have been on the horizon since May 2011, and all of that time, we have been expressing to the Government that this decision is a massive mistake. Cutting off access to therapy at 10 sessions goes against pretty much all of the research. As a psychologist who has conducted research, I feel quite strongly about the need to pay attention to evidence. It is negligent, irresponsible, and extremely risky, to draft mental health treatment policies based on opinion alone.

The cornerstone of our efforts has been to reflect with the Government about why this policy is a mistake. We have tried to do that by illuminating the research and helping the public understand why ten appointments of psychological treatment is not enough. We summarised the best reviews about the treatment of common mental health disorders. We also looked at studies that explore rates of recovery and clinically significant change, rather than relatively minor reductions in symptoms. All of the research comes up with roughly the same finding. That is, the most sensible solution for people who have a mental health condition is to offer around 20 appointments, and if people don’t need that length of treatment, the appointments they don’t use wont cost us a thing.

So it came as a bit of a surprise to us when a few months ago we were forwarded a reply from the Minister for Mental Health, claiming that, “Research has demonstrated many people with anxiety or depression will respond to 10 or less psychological treatment sessions”. The Minister cited the Tolkien II report, which he suggested indicates that offering less than 10 sessions is adequate for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety. This had us confused, because his claims seemed to go against all of the research that we had put on public display. I knew that there had to be some mistake, so I ordered myself a copy of that report.

A few weeks later the Tolkien II report arrived in the mail (as fate would have it, just before I saw The Hobbit at the movies). It was about as thick as a book from the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but nowhere near as entertaining. I was keen to learn how the Minister could possibly back up his claims.

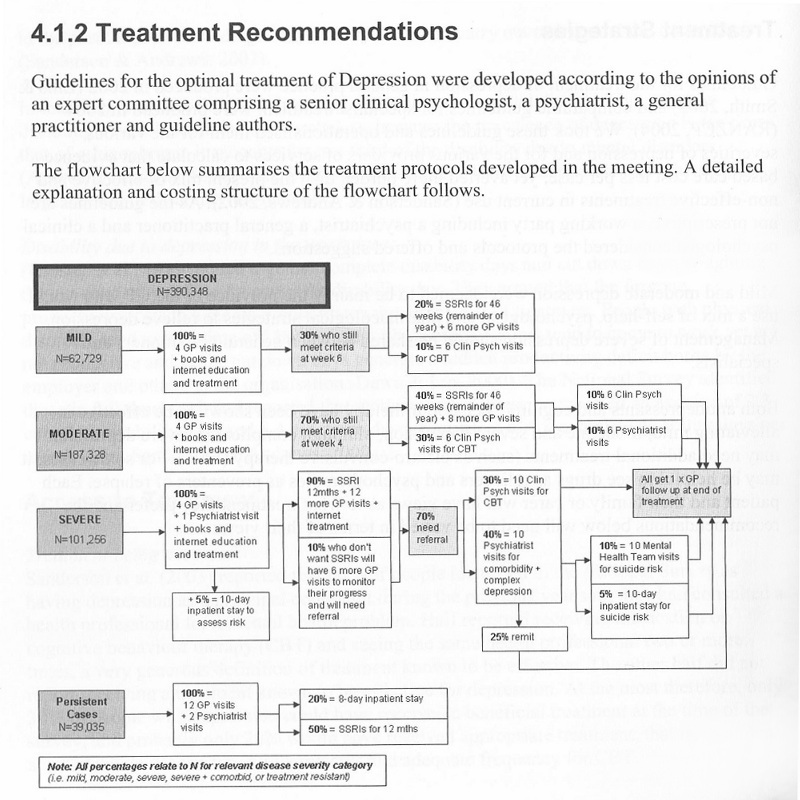

The report contains chapters dedicated to 13 different mental health disorders, broken down into sections titled: clinical pathway, treatment recommendations, cost structure, and references. Each section suggesting recommendations for treatment has a flow-chart. Pictured below is the flow-chart for the treatment of depression (right click and ‘view image’ to get a closer look).

The flowchart above (much like all of them in the Tolkien II report) reveals that the author held a meeting to get the opinions of a psychologist, a psychiatrist, and a GP, where he asked them to suggest what type and duration of treatment they should have access to across different levels of symptom severity. It indicates that the recommendations of the Tolkien II report are not based on research, but rather, from the opinions of the small group of mental health practitioners who were consulted. This begs the question of how different those recommendations might look if other people were asked and whether those opinions stack up against the evidence from research. With the report in hand, I only needed to flick back a few pages to read about some of that research. A quick glance at the research mentioned in the Tolkien II report confirms that there is a wide discrepancy between what they concluded and what the research actually shows about the amount of treatment needed.

For example, in the ‘Clinical Pathway’ section of the report, they mention a review conducted by Ellis and Smith (2002) for BeyondBlue, which states that at least 8 appointments should be offered even for the most mild and uncomplicated cases of depression. The review goes on to say, “The best outcomes are likely when a good therapeutic alliance is forged between a healthcare professional and the patient, and adequate treatment is provided over a long enough period” (underline added). More to the point though, BeyondBlue (our national depression initiative in Australia) has published A Guide to What Works for Depression which states that up to 24 appointments of psychological treatment may be needed (p. 21). Going by the flow chart in the Tolkien II report however, the maximum amount of psychological treatment they suggest is 12 visits. Should we believe the opinions of a few mental health ‘experts’ who hold the view that people with depression need an absolute maximum of 6 to 12 appointments, or should we go by the evidence from research indicating that people need access to more like 12 to 24 appointments?

Similarly, the Tolkien II report cites the clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depression produced by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP). The RANZCP guidelines are drawn from an extensive number of studies, with the reference list containing over 200 pieces of research. They recommend that we should provide access to a bare minimum of 12 appointments of psychological treatment, even for mild cases. The RANZCP guidelines suggest that when the condition of a person does not improve adequately within 12 sessions, people with depression should be referred back to the GP with an option for continuation of regular treatment for at least 12 months. The guidelines highlight that continued treatment improves psychosocial outcomes and stresses the point that continued psychological support reduces the rate of relapse. It’s the same conclusion, and what stands out most in both cases is the finding that a patient should not be prematurely cut off from psychological treatment. Yet that is exactly what the new cuts to Medicare will do by April this year.

Coming back to the main issue, what we have in Australia right now is a Federal Minister for Mental Health who is claiming that research supports his decision to limit psychological treatment to just 10 appointments. But when you check the source of his claims, it turns out that the report he cited did not factor in research about the duration of treatment at all. Instead, the author of the report asked a handful of mental health practitioners for their opinions. That’s what his decision is based on, not the research. To make matters worse, the report being cited by the Minister draws conclusions that don’t even align with the conclusions of the reviews they cited in the same paper. And that brings us to the key problem with relying on opinions. It takes us to a place where we can simply overlook the evidence from hundreds of studies, spanning several decades, where thousands of real people offered us a chance to appreciate what really works. It has us turn a blind eye to our best attempts at making sense of how to deliver appropriate mental health care.

There’s still a place for opinions in generating theories. But those theories need to be put to the test. Even when a highly intelligent person comes up with an idea, we need to show that it can work before we expose the public to treatment policies which may actually end up doing more harm than good. Every policy-maker, including the Minister for Mental Health, needs to hear us on this point. The Australian public deserves a system that is supported by the evidence, not something that is simply made up from the opinions of a few influential people. If you share our view that we need a mental health care system based on the evidence, then please sign our petition.